Growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, Montgomery was a city I passed through on the way to the beach or visited on grade school field trips to the state capitol building. I even visited the governor's mansion on one of those field trips. George Wallace was governor at that time but we schoolkids didn't get to meet him. We barely cared since we had only the faintest idea of who he was – our wheelchair-bound governor.

A few decades later, I took an adult interest in finally visiting Montgomery properly after I heard about the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, aka "the lynching memorial." Being a Birmingham native and longtime Georgia resident, I had witnessed my hometown grow from afar and come a long way to shake off the vestiges of Jim Crow and Bull Conner to become a thoroughly modern Southern city. After hearing similar things about Montgomery coming to terms with its past, I visited to check out some important legacy sites.

Situated on a sweeping horseshoe bend in the Alabama River, downtown Montgomery was once a major center of the domestic slave trade in the antebellum South. Enslaved people were transported on the river, unloaded at the dock, marched up Commerce Street and sold-off at the market on Court Square.

Today, there’s a beautiful circa-1885 fountain in the middle of Court Square adorned with frolicking figures from Greek mythology. Standing by the fountain and its soothing sounds of falling water, witnessing modern American life go on around you, it’s hard to fathom all the human suffering that once took place at this spot when people were treated like chattel and families were torn apart. So many slaves were trafficked through Montgomery that depots were built to warehouse them until it came time for the auction block. And, of course, it was all legal.

The fountain at Court Square with a view up Dexter Avenue toward the state capitol.

To help make sense of such a troubling history, I headed to the Legacy Museum, located one block away on the site of an old slave warehouse. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit organization that provides legal support to those who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced or abused by the prison system, opened the museum in 2018. The first thing you see upon walking inside are the words, "From enslavement to mass incarceration" over the entryway. That phrase provides a clue that you aren't entering an ordinary history museum but going on a journey from then to now.

The museum’s galleries chronicle racial injustice in the United States, beginning with replicas of pens where enslaved people were kept in the warehouses. High-tech displays and video consoles continue the journey through the Jim Crow era up to today’s crises of mass incarceration and police brutality. Touring the museum is a somber experience as you learn about the darker chapters in our history, the myths of racial inferiority and white supremacy that propelled them, and how these false narratives evolved to shape present-day attitudes.

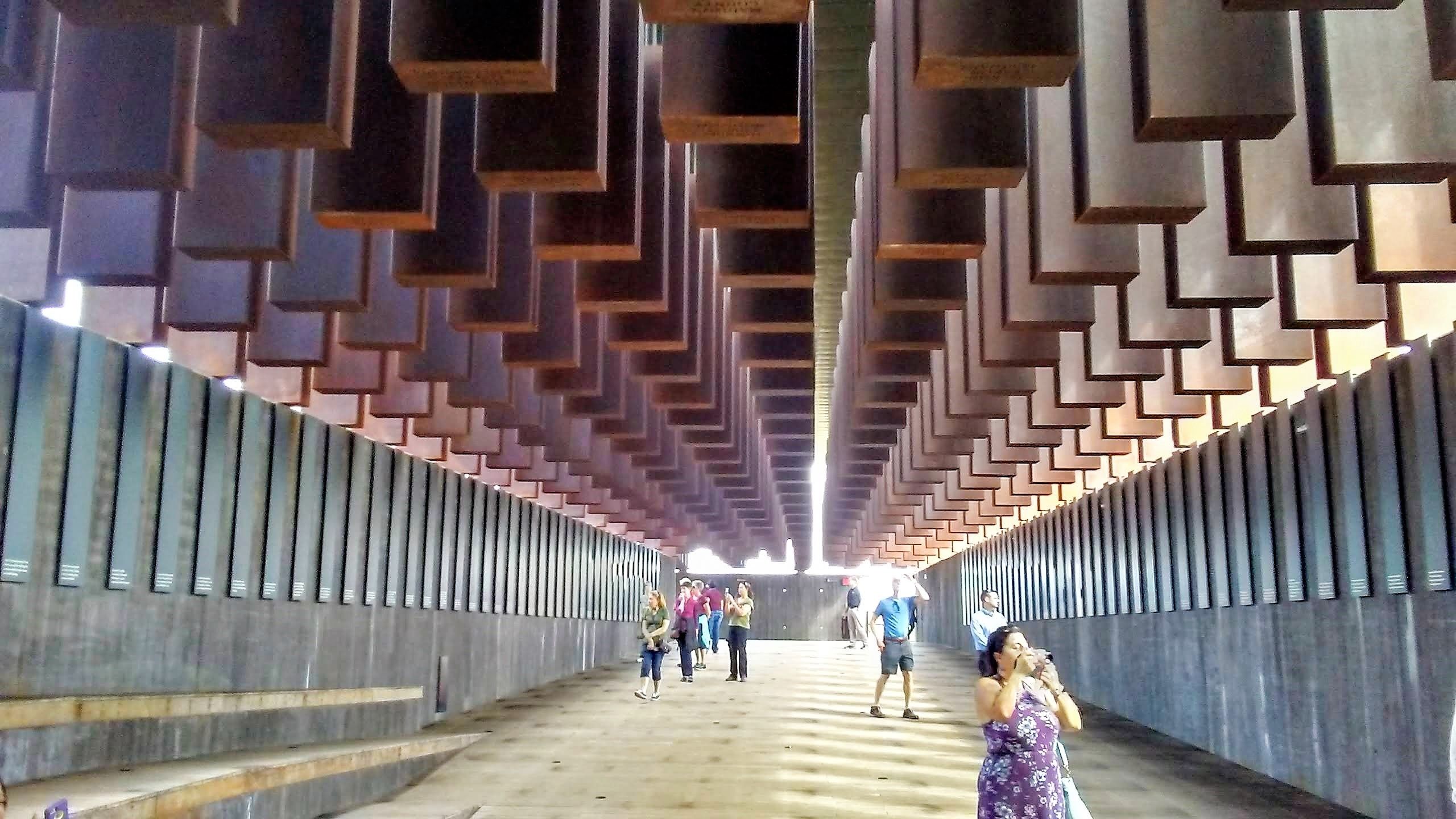

After a tour of the museum, I proceeded less than a mile away to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a sister site to the Legacy Museum. Located on a hillside overlooking downtown, it's a memorial to the 4,400 African Americans who were lynched in this country between 1877 and 1950. Red-rusted steel monoliths hang from the rafters of the open-air complex. Each monolith represents a county in the United States where documented lynchings took place. The names of the victims and the dates of their deaths are inscribed, thereby making each monolith a monument. The number of monuments above your head boggles the mind and stirs the soul.

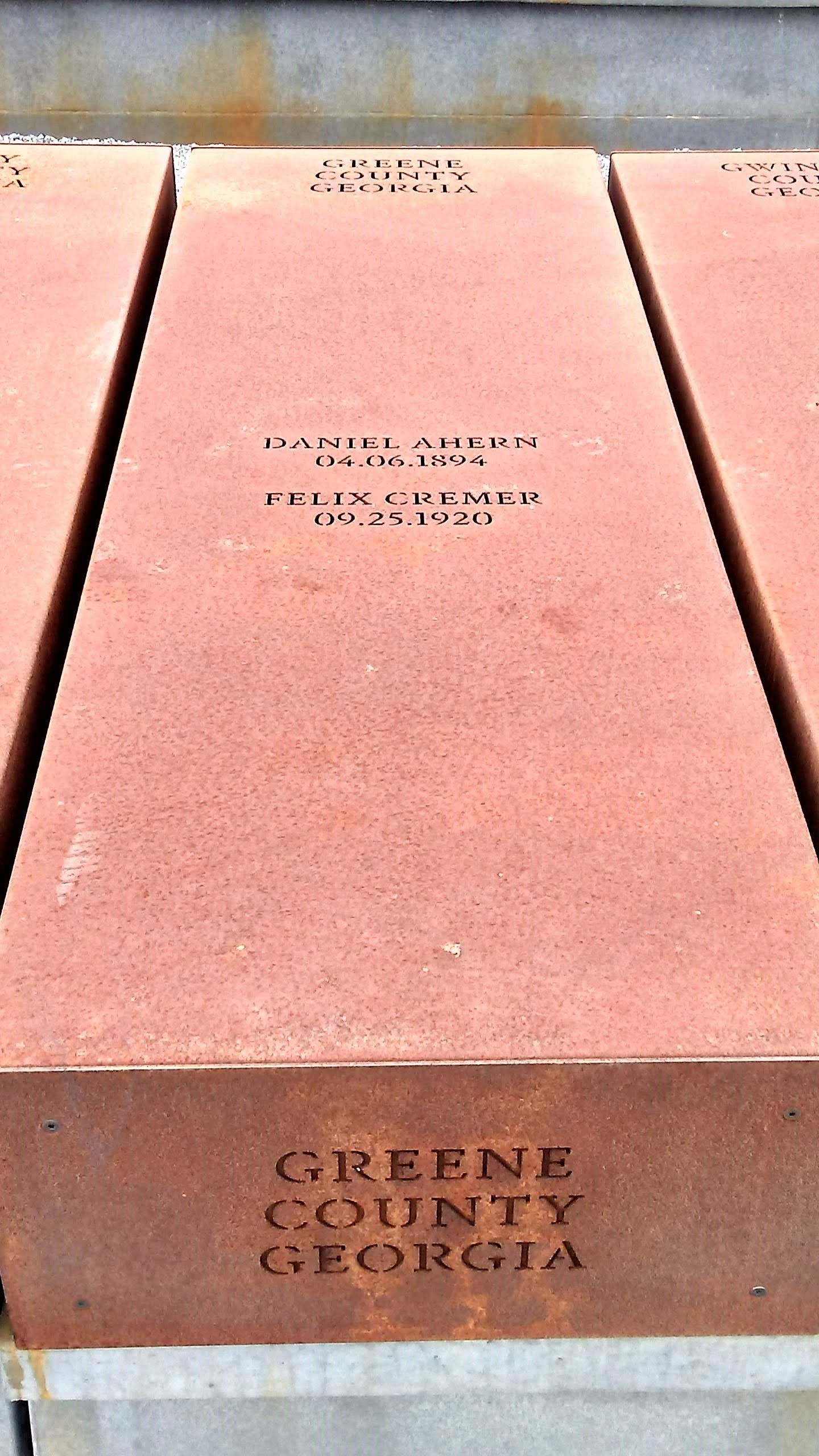

For each monument hanging inside the complex, a corresponding one lies on the ground outside, awaiting the county to claim it via the EJI's Community Remembrance Project. The project aims to foster dialogue and raise consciousness at the local level where lynchings occurred. Greene County, Georgia, where I currently live, had two names inscribed on its monument. Jefferson County, Alabama, where I was born and raised had 29 names inscribed on its red-rusted box. The names on the boxes are of lynchings that have been documented, a list that could change if more evidence comes to light.

Also on the six-acre grounds are stark, life-sized sculptures depicting enslaved people in bondage and, near the end of the pathway that leads through the site, African American domestic workers walking to the homes of the white families that employed them. These figures represent the foot soldiers and unsung heroes of the seminal Montgomery bus boycott of 1955. The sculptures stand in the middle of the pathway, so it’s as if you’re walking alongside these determined women.

A life-sized sculpture of slaves in bondage at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

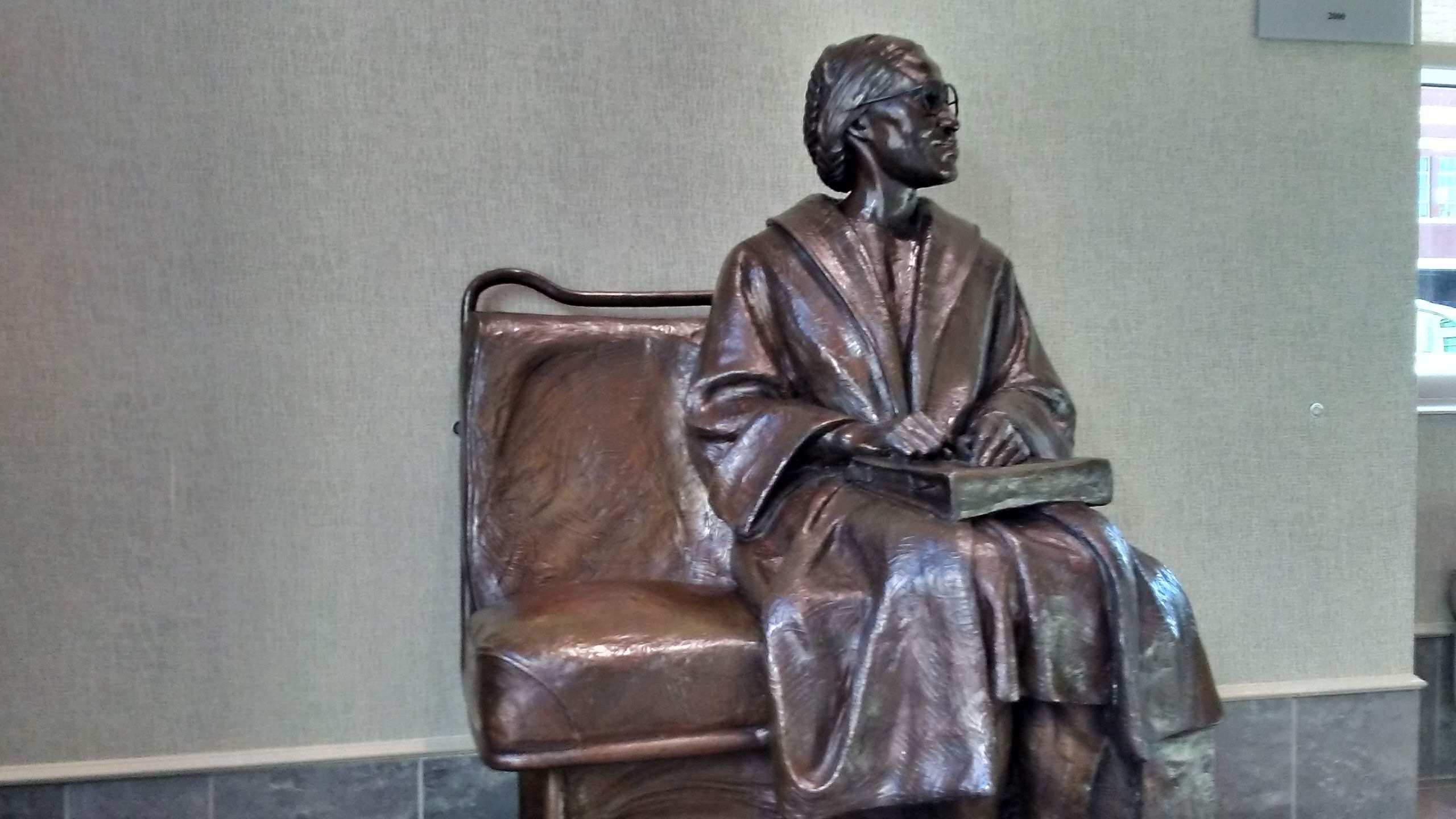

The bus boycotts are also at the center of the Rosa Parks Museum, located on Montgomery Street between the two EJI sites. When Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a city bus, the boycotts were sparked and the modern civil rights movement was born. The museum includes a display containing the original arrest report that includes Parks’ fingerprints. There’s also a restored public bus from the era. A unique large-scale video with actors re-enacts the events of that fateful day inside the bus while visitors stand outside and watch it unfold. A historic marker on the sidewalk in front of the museum designates the spot where Parks was arrested.

A statue of a hero greets visitors at the Rosa Parks Museum in downtown Montgomery.

A statue of a hero greets visitors at the Rosa Parks Museum in downtown Montgomery.

The boycott also brought to prominence a young pastor from Atlanta who had recently moved to Montgomery to become pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. became a leader of the boycott and held mass organizational meetings in the church where he served from 1954 to 1960. Now called Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, it’s a National Historic Site open for tours and still an active church. The church looks the same inside and out as it did during King’s time, and his basement office is kept exactly as it was then, including the books on the shelves and the rotary phone on the desk.

A stained glass window in the sanctuary of Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church.

A stained glass window in the sanctuary of Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church.

Other notable nearby sites connected to the civil rights movement are the Dexter Parsonage Museum where King and his family lived during his time as pastor – the house, which was bombed several times during the movement years, appears as it did when the young King family lived there; the Freedom Rides Museum housed in the old Greyhound bus station where the Freedom Riders were attacked in 1961; and the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial that pays tribute to those who died in the civil rights struggles between 1954 and 1968.

Back at the Court Square fountain, you can look straight up Dexter Avenue and see the sites where many historical events transpired. To the immediate right is the building where the order was telegraphed to fire on Fort Sumter, thereby starting the Civil War. At the top of the hill looms the state capitol building, where the final march from Selma ended on March 25, 1965, and King delivered his famous “How Long, Not Long” speech within view of the church where he once served as pastor. The speech contains the oft-quoted line: “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Apropos words, given the location. From slave auctions to civil rights marches to the homes of the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery has come a long way in bending that arc in the right direction.

If you go

Sites

The Legacy Museum. 400 N. Court St.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. 417 Caroline St. 334-386-9100, museumandmemorial.eji.org.

Rosa Parks Museum. 252 Montgomery St. 334-241-8615, www.troy.edu.

Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church. 454 Dexter Ave. 334-263-3970, www.dexterkingmemorial.org.

Stay

Renaissance Montgomery Hotel & Spa at the Convention Center. $249 and up. Downtown Montgomery's largest hotel, this comfortable Marriott property is within walking distance of all the sites mentioned in this article. 201 Tallapoosa St. 800-468-3571, www.marriott.com.

The Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald Museum. $130 and up. One of the more unique accommodations in Montgomery, guests stay in the upstairs portion of the home where Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald lived in the early 1930s. Downstairs is a house museum dedicated to the Fitzgeralds. The upstairs contains two separate period suites. No TVs but Wi-Fi is available. 919 Felder Ave. 334-264-4222, www.thefitzgeraldmuseum.org.

Visitor info

Montgomery Area Visitor Center. 1 Court Square. 334-262-0013, visitingmontgomery.com.

– Blake Guthrie. All photos by the author.